Game Theory and Snow Shoveling

My adopted city of Washington, DC, is shoveling out from under some of the last snow of the season. At the same time, we’ve just enacted a law that levies fines on residents who don’t clear their sidewalks, after years of debate.

There’s a very good reason to fine property owners for not shoveling their sidewalks. Snow shoveling is a what’s known as a multi-player prisoner’s dilemma. If everyone shovels, everyone is better off (because they can get around more easily, don’t face the danger of falls, don’t have to pay extra cleaning bills due to muddy/salty pant cuffs and skirt hems, &c.). However, any one person is better off if they don’t shovel, because they’ve saved time (I actually like shoveling my sidewalk, but let’s assume that the utility for shoveling is uniformly negative). Each individual isn’t affected much by the state of their own sidewalk, but rather by the state of everyone else’s.

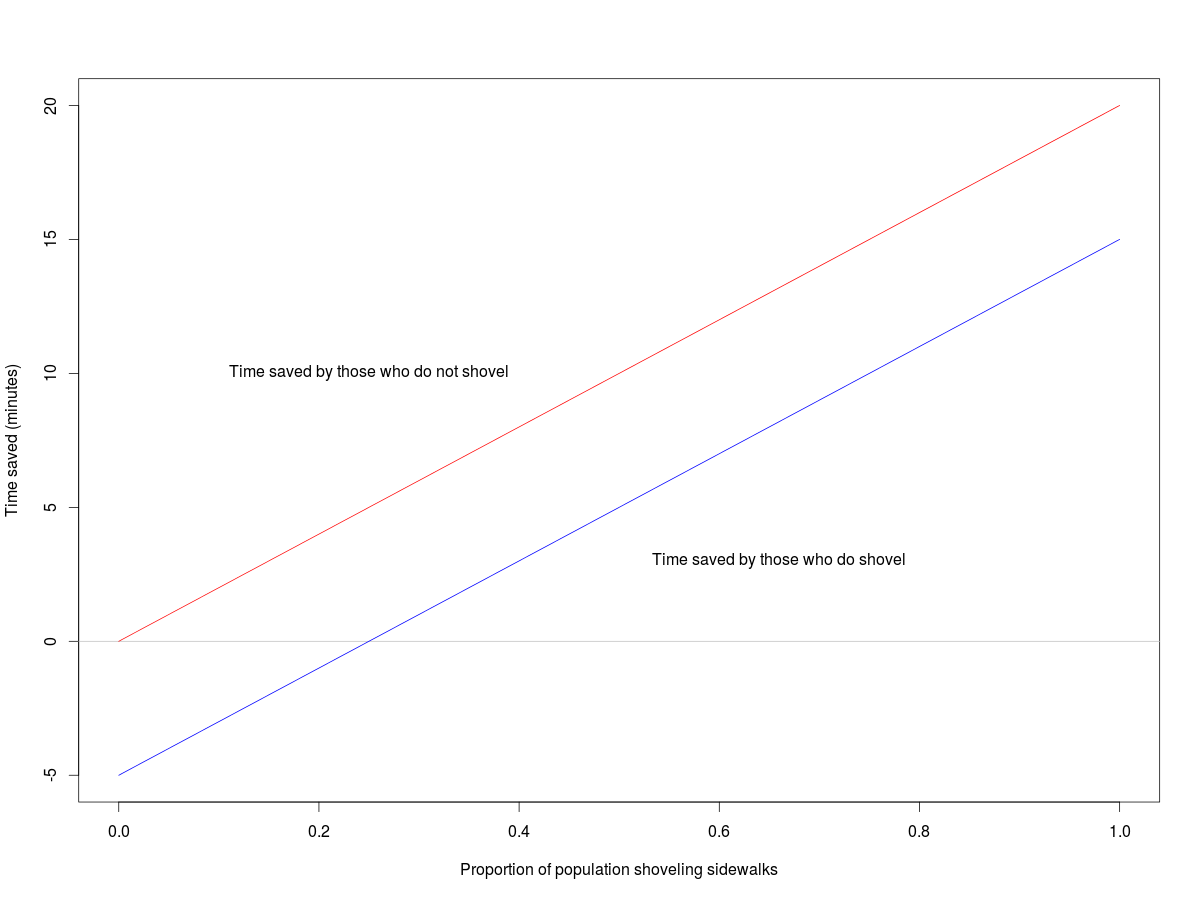

We can represent this issue graphically, as Thomas Schelling does in chapter 7 of Micromotives and Macrobehavior. For simplicity’s sake, let’s assume that the only benefit to shoveled sidewalks is a quicker walk to wherever you need to go. Let’s also assume that it takes five minutes to shovel your sidewalk, and that you can save twenty minutes in transportation time if every sidewalk is shoveled, as opposed to none. Finally, let’s assume that if half of the sidewalks are shoveled, you save half as much time: ten minutes.

The graph below shows how much time is saved by people who do not shovel (red line), and those who do shovel, as a function of how many people choose to shovel. The time is the amount of time saved commuting, minus the time spent shoveling. As you can see, at every point there is an incentive not to shovel, but take advantage of your neighbors’ shoveled walks. However, if everyone does that, you reach a situation where no one’s walks are shoveled, and no one is saving any time. If everyone’s walks are shoveled, everyone saves time despite having to spend time shoveling (the right end of the blue line). Since the second situation is clearly the preferable one, we need to have some system to encourage people to shovel. This could take many forms: a general sense of community standards, public shaming of those who do not shovel, or a regulation with fines attached.

We can carry the economic theory further, and say that the amount of the fine has to be greater than the distance between the two lines, but that’s not really a meaningful thing to do. For one thing, the distance between the lines is in units of time, while the fine is in units of money, two things that convert in wildly different ways for different people. Also, we must remember that the numbers we used were completely arbitrary and furthermore not uniform across the population.

Schelling also points out that there is a minimum viable coalition size, a minimum number of people who have to cooperate to shovel their sidewalks in order to realize a net gain. This is the point where the payoff curve for shoveling reaches the payoff that everyone would get if no one shoveled. In the figure above, at about 0.2, those who choose to shovel are better off than they would have been had no one chosen to shovel. This isn’t really a meaningful number here for several reasons. As mentioned before, the assumption of uniform arbitrary payoffs is invalid. Additionally, you are not equally affected by every shoveled sidewalk. A geographically dispersed coalition may be no better than no coalition, if no member of the coalition walks on the shoveled sidewalks of any other member. A geographically concentrated coalition may be viable even at small numbers, because the sidewalks being shoveled are the sidewalks most relevant to the members. (Consider a commercial strip where the business cooperate to shovel their stretch of road. Even though the coalition is small, its members benefit because customers can walk up and down their commercial strip).

Thus, fines for not shoveling are a way of encouraging a socially desirable outcome, when individual motivations would result in a socially undesirable outcome.